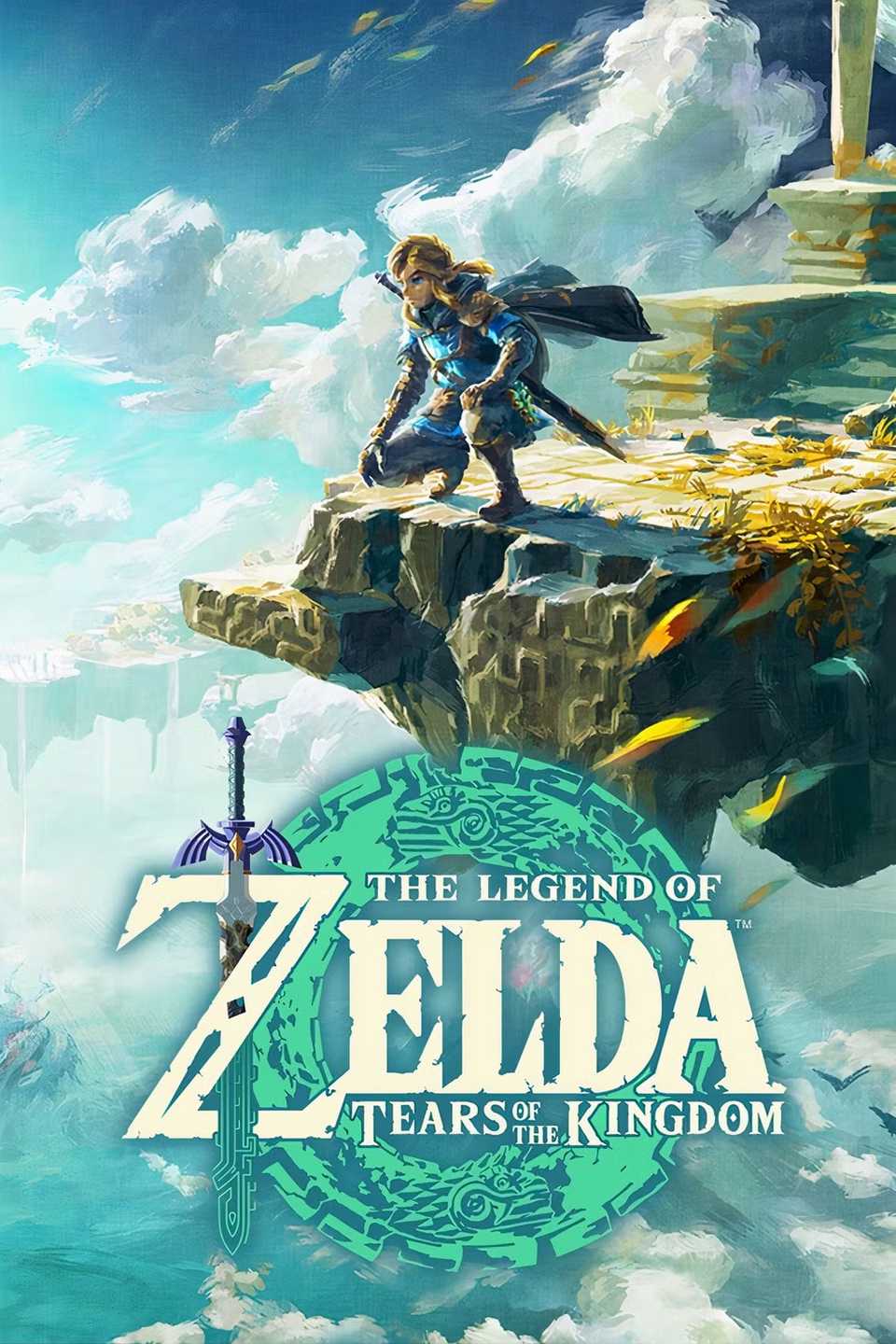

Few games make feeling lost as much fun as The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom does Players can glide from a sky island with a very clear goal in mind, only to veer off course after an undiscovered stable in the distance catches their attention. Upon reaching said barn, they may encounter eccentric NPCs who will want help tracking down their missing goats or finding out what happened to some borrowed farming tools. Before you know it, The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom it distracts the player with something completely different from what they originally intended; for the most inquisitive players, this cycle only continues from here.

Of course, this is the main part Tears of the Kingdom's appeal, with the fact that he rarely considers his vast world to be anything other than a curiosity. After its predecessor introduced the largest map ever created for the main series Zelda game, Tears of the Kingdom took it even further by adding two more Hyrule-sized layers with sky islands and depths. However, with all the scope and endless possibilities that come with it, there's something to be said for the earlier Zelda games that made exploration feel like a major part of progress rather than a constant stream of potential detours. 2006 Zelda classical Princess Twilightfor example, it made access to the world earned, turning Hyrule into a reward that unfolded over time, rather than a vast space that instantly opens up to distraction.

Twilight Princess made the world itself a reward

Unlike Zelda: Tears of the Kingdomwhich has given players almost unlimited access to its entire map almost since its inception in 2006 Princess Twilight rather, they used a drip method that caused the world to develop in stages. At the very beginning, in Ordon Village and Hyrule Field, players didn't have the tools or access to go everywhere right away, and the main world had limits that would only disappear as the story progressed. Exploration was possible, but many areas were shadow-locked, blocked, or otherwise inaccessible until certain story times were reached or specific items were obtained.

Princess TwilightFor example, the Forest Temple granted players the Gale Boomerang, which allowed them to reach new locations and solve global puzzles in a way they couldn't before. Later dungeons such as the Temple of Time and others also advanced both the story and how players would travel across Hyrule. Zelda: Twilight Princess' dungeons functioned as integrated progression checkpoints rather than mere obstacles, making clearing them as rewarding from a gameplay standpoint as it was from a narrative standpoint. Wolf Link's unique mechanics also allowed players to follow ghost trails, dig up secrets, and unlock shortcuts or buried doors that human Link hadn't been able to reach before, making exploration feel more layered than being simple from the start.

How Twilight Princess justified her gates

-

The game told players why certain areas were blocked

-

Gates were conceived as problems to be solved rather than walls to be bypassed

-

The gates have been permanently removed, not bypassed

-

Gating served the narrative rather than the gameplay

It can be challenging to justify such world design in modern games, simply because many players appreciate the freedom that games like Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom to offer them and artificial gating is generally considered a cardinal sin. However, Princess TwilightGating felt different because it was deeply contextualized, layered, and temporal. First, the game often told players why certain areas were blocked, as opposed to simply providing an invisible wall. Whether the land was corrupted by Twilight, Link wasn't in the right form, or it made narrative sense that the area was temporarily inaccessible, Princess TwilightGates were rarely unexplained.

Second, the game framed its world gates as problems to be solved rather than obstacles Princess Twilight sometimes feel like a metroidvania that still adheres to the traditions and Zelda game. If players hit a dead end while exploring the world, instead of thinking “I'm not allowed to go there”, the “I'll fix it later” thought process was more strongly encouraged. Third, each gate was permanently removed and not bypassed. Once a region or dungeon was cleared, players could forever progress to the next main region, showing the world as something that grew with the player's journey. On the other hand, they encountered a fulfilling sense of world development that coincided with the steady escalation of its story and mechanics.

and finally, Princess TwilightIn the end, World Gating served the narrative more than the gameplay. While the games have been known to prevent players from traveling to certain areas simply due to level or skill restrictions, their exploration has been delayed in line with their story. Ultimately, this is the main reason why they remember this building fondly Princess Twilight fans because his research was earned as if it served a greater purpose. And rather than being central to the game as it is in Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom's Hyrule, it was central to the narrative.

Tears of the Kingdom takes the world as its starting point

Instead of rewarding players with the world itself Tears of the Kingdom he buries his most grateful elements in the world. If Princess Twilight it begins as a closed book ready to be opened Tears of the Kingdom it's like reading a book backwards. If Princess Twilight it's like walking down a buffet line piling food onto a plate Tears of the Kingdom it's like taking small bites of the food and slowly discerning its ingredients. This is not inherently a bad thing Tears of the Kingdom to be built this way, but it's been a huge game changer since Princess Twilight.

It progresses through Princess TwilightThe story is about unlocking parts into a greater whole Tears of the Kingdom it is about taking apart the puzzle and thoroughly examining the individual identity of each piece. That means research in Tears of the Kingdom it is driven by curiosity rather than progression. Players rarely work for access or wait for the world to acknowledge their growth, as most of Hyrule is already willing to meet them wherever they are. Instead, familiarity, systemic mastery, and personal stories born of detours and experiments are gained. It creates a strong sense of freedom, but also explains why some players look back Princess Twilight and think of Hyrule, which felt like it was slowly opening its doors in response to their journey, rather than standing wide open from the start.

Of course, it's an entirely apples and oranges argument, because even though Princess Twilight gives his survey a sense of merit and Tears of the Kingdom takes the opposite approach, the latter still makes the act of exploration a fulfilling experience. The difference is not which approach is better, but what each game requires players to appreciate. Princess Twilight it combines exploration with momentum and uses restraint to make each newly opened section of Hyrule feel like a reaction to progress. Tears of the Kingdomon the other hand, it trusts player intrigue and lets meaning emerge through discovery rather than access. Both succeed on their own terms, but leave very different impressions. One remembers where they finally arrived, while the other remembers all the unexpected places they wandered into along the way.

The Twilight Princess Drip-Fed survey still has value in a post-TotK world

Eventually, Princess Twilight stands out among Zelda games and contemporaries not because it limited players but because it gave a progressive purpose. Each newly opened area reinforced the sense that Hyrule responded to Link's journey rather than simply existing around him. Tears of the Kingdom excels in challenging players to get lost, experiment, and choose their own path, but Princess Twilight is a reminder of a time when seeing more of the world was a reward in itself. For players who appreciate that constant sense of arrival and growth, his approach to exploration still holds value nearly two decades later.

- Released

-

May 12, 2023

- ESRB

-

Rated E for ages 10 and up for fantasy violence and mild themes

- Developers

-

Nintendo

- Publishers

-

Nintendo